What and how many resources does it really take to raise a newborn baby to productive adulthood? And who pays for it?

These are questions of primordial importance as they pertain to demographic renewal and fiscal sustainability—to how societies reproduce over time. In a study in Royal Society Open Science, demographer Robert Gal, sociologist Marton Medgyesi, and I use new accounting methods for 12 European Union countries to measure not just all public transfers (the “state”) but also the less visible flows of private time (e.g. parental care) and money (e.g. market goods and services).

This allows us to better measure the production of economic value, too. GDP, for instance, still does not count unpaid household labour. As care economist Nancy Folbre and others have argued, economic statistics today render enormous amounts of unpaid care work invisible, even though firms and governments could not function without the human capabilities and fiscal revenue created by care work.

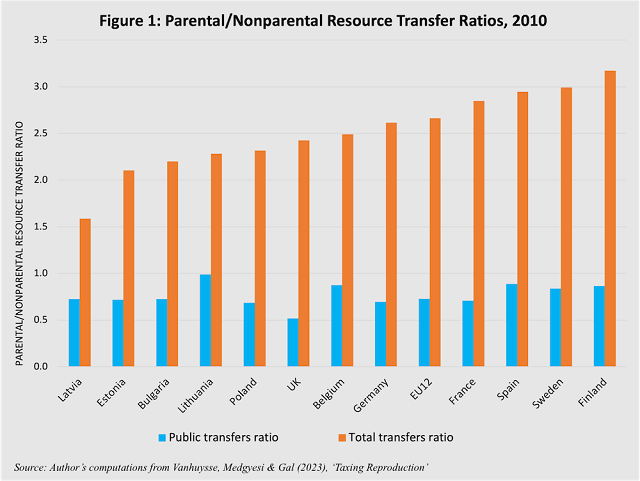

Better accounting for intergenerational transfers truly shifts perspectives, and not just marginally. As Figure 1 shows, parents in Europe contribute somewhat fewer public transfers than non-parents—the blue bars, which capture all taxes and social security contributions paid, net of all benefits received (channel 1). The parental/nonparental ratio in public transfers is below 1 everywhere in Europe.

But away from the statistical limelight, parents (and only parents) additionally provide very large private transfers of time (unpaid household labor) and money (market goods and services) to their own children. The parental/nonparental ratio in total resource transfers (the orange bars) jumps up to well above 1 everywhere in Europe. In fact, this ratio is above 2 in 11 out of 12 countries in the sample.

This might seem unremarkable. Parents are, after all, the primary caretakers. What is remarkable is that these hidden extra transfers are so large that they radically change the entire picture. Over an entire working life, the average parental/non-parental contribution ratio in Europe flips around, from 0.73 when measuring public transfers alone (the blue bars; channel 1), to 2.66 when including all three transfer types (the orange bars; channels 1, 2 and 3 together).

In other words, Gal, Medgyesi and I show that parents contribute about one-quarter fewer net taxes than non-parents. But when we then also value all flows of time and money, it turns out that parents contribute more than two-and-a-half times more resources overall. It takes a village, said Hillary Clinton. As we show, it certainly takes taxpayers, but even more so, parents.

Debunking Another “Stork Theory”

Why do such large asymmetries in cost-sharing matter? Rearing children is not just a personal lifestyle choice. Children are also public goods. As they grow up to become taxpayers, social security contributors, caregivers and parents in their turn, children will finance future public goods and welfare states. All of this will then also benefit non-parents.

Hence, childrearing creates positive externalities. To be sure, not all parental inputs carry such externalities: some part resembles pure consumption. Parental transfers may also reduce intergenerational mobility. So why should parents be compensated for the high transfer cost of something they presumably freely engaged in?

A key reason is that not counting the positive externalities of a good generally leads to socially suboptimal amounts of that good being produced. If societies do not fully value the transfer cost of childrearing, they risk producing too few productive adults. This puts the intergenerational social contract under severe strain. Ultimately, labor markets and welfare states could not continue to function well without the value produced by families. In Alfonso Cuarón’s cult sci-fi thriller Children of Men, two decades of infertility have brought society near collapse.

Even in the most liberal societies, everyone, irrespective of their personal conception of the good life, has a strong interest in having someone produce the next generation of workers and taxpayers. Barring immigration on a politically wholly unrealistic scale, the renewal of the fiscal basis of the welfare state crucially depends on sustainable demographic reproduction.

This is a function of both the size (“quantity”) and the productivity and capabilities (“quality”) of successive generations—of what mainly parents do. This is why childrearing acquires the deeper status of producing a socially necessary public good. This creates stronger moral obligations for all those who benefit to share in its cost.

It is the relative invisibility of parental time and money transfers that allows welfare states to freeride on the cost of producing the next generation of workers and taxpayers. Today, policy practices do not fully take into account how the human and fiscal resources welfare states and labour markets tap into were created in the first place.

We argue that societies thus adhere to a sort of “stork theory” that needs debunking. Just as newborn infants are not actually delivered by storks, new resource-productive adults do not just drop fully formed out of the sky. Rather, they are delivered to society after a further 25 years of child-rearing, financed to some degree by all taxpayers but to a larger degree by their own parents. Parents are not compensated for most of these contributions.

Parental Prisoners of Love

Better measuring the distributional impact of the status quo would allow debates about the social and private costs of demographic renewal to be held on more complete and more explicit terms. Many activities with positive externalities, such as charitable donations, private savings or investments in green technologies, are awarded tax credits. In Ancient Rome, tax laws recognized childrearing as an activity fiscally equivalent to paying taxes. The poorest Roman citizens were tax-exempt but were considered to contribute in kind by rearing their offspring. They were called proletarii: men who could serve the public only by fathering children (proles).

If societies do not fully value the transfer cost of childrearing, they risk producing too few productive adults. This puts the intergenerational social contract under severe strain.

But when parents produce positive externalities today, instead of receiving tax credits, they shoulder a significant extra resource contribution load. We calculate that the “tax” rates implicitly imposed thereby on childrearing are much higher than the value-added tax rates currently in place in Europe on consumption goods such as food, clothes and electronics. As Nancy Folbre paraphrases our work: in practice, aging societies are unwittingly taxing the stork.

There is something quite wrongheaded about two other widespread societal (non-)valuation practices: the “motherhood penalties” and “carer penalties” in labor markets. Mothers love their children and carers love their jobs. These, too, are presumably freely chosen pursuits. Yet making mothers and carers pay an earnings penalty is akin to freeriding on that love: a form of exploitation. This is neither just nor efficient. Folbre put it memorably: when societies take “prisoners of love,” it does not benefit them in the long run. This is an unsustainable policy. Our work indicates that societies also take parental prisoners of love. Is this good policy?

Why Aren’t Societies More Family-Friendly?

Better accounting for invisible value production matters as it substantially changes how we understand, let alone address, the same policy question. This applies to care work and motherhood. It applies to green growth. And it also applies to the transfer cost of producing the next generation of workers and taxpayers. Children are partly consumption to their parents, but they are also a socially necessary public good.

When parents contribute over two-and-a-half times more resources than non-parents, this captures the sheer magnitude of the asymmetric cost-sharing. The private resources parents give their children may be statistically less visible, but they are no less real—and no less essential for social reproduction.

The same resources could have been spent otherwise, in more consumption or savings. Unlike savings, the private transfer cost of childrearing really is a cost and only metaphorically an “investment.” Parents do not get to keep the capital they spend, nor do they receive positive returns for it. The large size of this “privatized” cost will affect parenting decisions and lower fertility levels.

So, it is no wonder that many young people today aspire to become DINKs – Double Income, No Kids – even though this approach would be self-defeating if generalized. And it is no wonder that parents will think twice when considering whether to have that first, or second, child.

Toward a More Holistic Human Capabilities Policy Paradigm

In sum, we need to be clearer about all it really takes to rear a child to a ‘quality’ adult who is productive, mentally healthy, and fiscally and socially responsible. We need to understand better what it would really mean for a welfare state to be family-friendly. And we really need to think harder, and be more explicit, about what we really want to value in our aging, low-fertility societies.

This raises important questions about policy models in an aging Europe of elderly-oriented welfare states. Across Europe, parents have significantly fewer children than they would like. Of course, we are nowhere near the zero-fertility dystopia of Children of Men. But Europe has, for a while now, grappled with fertility rates well below replacement level, high or still-increasing levels of childlessness, and larger, longer-living elderly populations. Yet despite rising demographic tensions, societies unwittingly tax rather than subsidize their own reproduction. In the long run, this is an unsustainable policy.

To secure its future foundations and avoid becoming a continent of gerontocracies, Europe needs to make its policy models more intergenerationally balanced and much more human capital-oriented. For despite its name, the quarter-century old “social investment paradigm” spearheaded academically by Nobel laureate James Heckman and others is actually still very incomplete in our policy models (mainly channel 1). We need more holistic policies to better assist, value, and incentivize the reproductive contributions of parents, carers, and educators—those who nurture the human capabilities that will later sustain us all.

Pieter Vanhuysse (PhD, LSE) is a member of the European Academy, a Full Professor of Political Economy and Public Policy at the Department of Political Science and a Chair at the Danish Institute for Advanced Study, University of Southern Denmark. He works on political economy, welfare states, political demography and intergenerational transfers.

*Photo credit: Shutterstock