I was still in college and in my early twenties when I started thinking about when I wanted to get married. There were several pieces of advice that floated around from sources, both seen and unseen. Divorce statistics, in particular, were scary. Some sources suggested that if you waited until you had your degree, your marriage would be safer from divorce and happier. Others added that you needed to be older and more mature to avoid divorce or a bad marriage.

Partly influenced by my religious background and my close relationship with my parents, I decided I wanted to get married anyway. When I started dating my future spouse and we began talking about marriage, I mostly felt at peace about it, but there were moments when the fear crept in about divorce due to occasional tension in our relationship. Despite this fear, I decided to take a marital leap of faith.

Since then, I have learned a lot more about marriage and divorce. The prominent family sociologist, Andrew Cherlin, notes that marriage is changing its place in adult development from a cornerstone to a capstone. Instead of a consistent, tried-and-true, socially-prescripted sequence of milestones leading to marriage, there is no one road to travel and no particular timetable.

Most young adults, however, are delaying marriage. The national median age at first marriage now is 28 for women and 30 for men. Increasing age at marriage is not the only change. Divorce rates are also decreasing, and fewer people are marrying. However, most young adults and high school seniors desire to marry (although fewer high school seniors now think that they will).

While the age of marriage has risen substantially, the connection to marital stability has not been closely examined for a few decades. We know that teenage marriages continue to have a higher divorce risk, although their frequency has decreased. One 2012 study found that for individuals marrying at ages younger than 25, there is a slightly increased risk of divorce within the first five years of marriage compared to those marrying at 25 or older.

Some have linked the increasing age at marriage to lower divorce rates because of an influential study that found early marriages have a higher divorce risk. But this study is more than three decades old. Does this association hold true for recent cohorts? Also, past research has only explored the link between early marriage and divorce; a broader picture of marital quality in early marriage is curiously absent. Thus, a more up-to-date study is needed.

As part of my graduate studies, I wanted to pursue a couple of questions: (1) Is marital quality in the early years of marriage lower for those who marry at earlier vs. later ages? (2) Are those who marry at earlier ages more likely to divorce (within 5 years) than those who marry at later ages?

To investigate these questions, I used the Couple Relationships and Transition Experiences (CREATE) study, a longitudinal, national probability sample of newlywed couples in the United States who married in about 2015. At least one of the partners had to be in their first marriage to participate in the study and be at least 18 years old. There were about 1,900 women and 1,700 men in my analytical sample. Participants’ ages at first marriage ranged from 18-53; only 7% married before age 20 and only 5% married after age 35. One-third married between 20-25, 37% married between 26-30, and 17% married between 31-35.

I used a wide array of marital quality measures (totaling 16) to get as rich a view of their relationships as possible, such as forgiveness, relationship communication, conflict management, relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, marital instability, and divorce. In my regression models, I also employed several statistical controls, including marital timing beliefs, religious orientation, children present at wave 1, race, education, cohabitation, and parental divorce.1

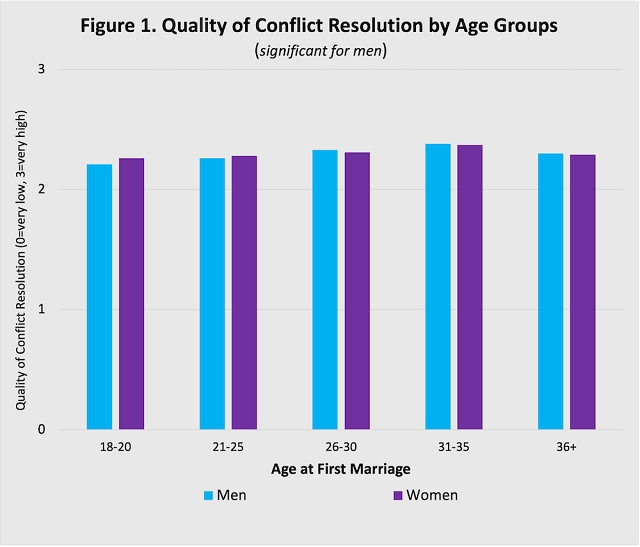

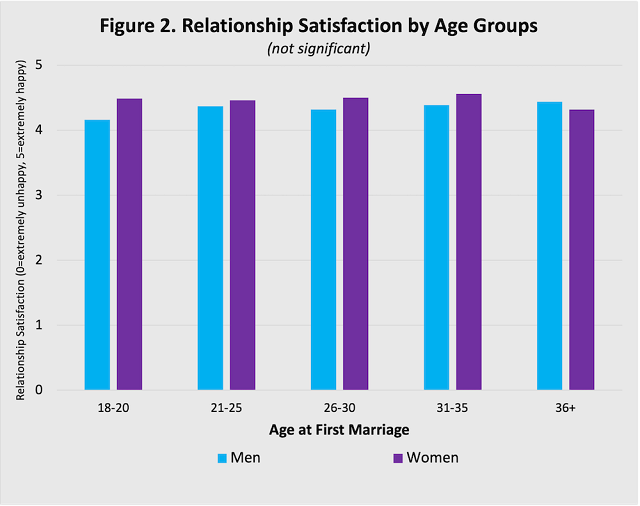

Overall, I found few significant links between age at marriage and marital quality for women or men. When statistically significant relationships emerged, they were relatively weak. For instance, Figure 1 demonstrates a typical gentle, curvilinear relationship between age of marriage and men’s and women’s reported quality of conflict resolution. Also, while most men and women were happy in their marriage, age at marriage did not significantly influence their marital happiness (Figure 2).

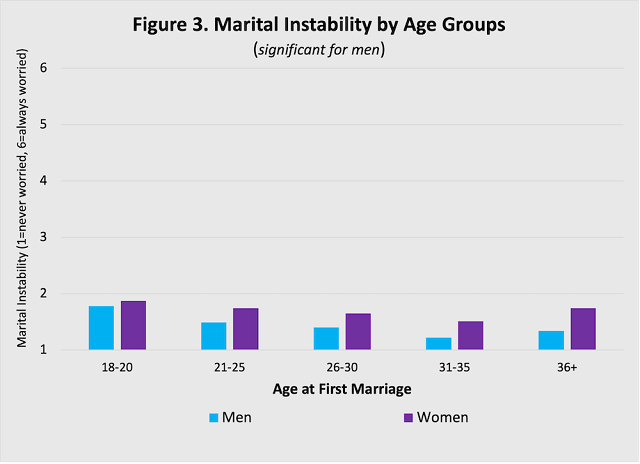

The biggest difference is depicted in Figure 3, in which the data hint at the possibility that younger marrying men (up to age 25) may be more worried about the future of their relationship than men who married in their late 20s and early 30s. (Those who married very late reported the most concerns about marital stability.) There could be a number of reasons for this. For example, younger men are experiencing a lot of physical and life developments. The prefrontal cortex is not fully developed until the mid-20s, which can impact the regulation of thoughts, actions, and emotions. College education and career establishment are also taking place for younger men. If children are added into these important developmental issues, it may push younger men to worry more about the success of their relationship.

As motivations for marriage and societal pressure to marry have changed over the past few decades, the decision to marry has become more of a personal choice than a social norm. With this study, I found that age at first marriage in a nationally representative cohort of recent marriages had weak to no influence on marital quality. I found that other factors, such as the presence of children, are a much stronger predictor of marital quality than age at marriage. Maybe those who do marry early, like me, do so not because they have to get married but because they want to get married. There clearly is less pressure to marry young; in fact, young couples in love probably feel social pressure to delay a marriage.

In this research, I found little support for the widely-accepted idea that marrying in your early 20s produces lower quality marriages. But is earlier marriage still associated with a higher risk of divorce, even if has little effect on marital quality? Again, I found little evidence in this sample to support this general belief that early marriages are at greater risk for breakup, but it is possible that sample attrition over 5 years was biased by those who were more likely to divorce.

So, maybe this question is better addressed by findings from recent research by IFS Fellows Lyman Stone and Brad Wilcox using the National Survey of Family Growth. This study explored the complex relationships between age of marriage, cohabitation, and religiosity on risk of divorce. The researchers found that teen marriages and later-life marriages still hold the highest risk for divorce. But for religious women, marrying in their early- or mid-20s did not increase their risk of divorce, probably because it reduced their likelihood of premarital cohabitation, which is a strong risk factor. However, for non-religious women, they reduced their risk somewhat by waiting until their late 20s to marry.

The bottom line in all this, I think, is that age of marriage is not the potent, straightforward predicator of marital outcomes that it apparently was a generation or two ago when marriage was a crucial signpost of adulthood, and premarital sex and nonmarital births were frowned upon. Young adults today would do better to focus on other factors to understand their chances of marital success. Parents, too, worry about their children’s age at marriage and have been shown to encourage them to wait until they are older. However, these worries may be misplaced today.

Instead of focusing on age, parents can encourage their children to develop good communication and other relationship skills. And when children in their early 20s fall in love and want to build a life together with someone, parents (and friends) can be supportive of a young adult’s choice to marry rather than withholding support or encouraging them to delay tying the knot. Maybe this kind of support can help stem the trend of decreasing marriage rates because sometimes marriage delayed is marriage foregone.

Anne Marie Wright Jones recently received her master’s degree in Marriage, Family, and Human Development at Brigham Young University. She thanks Drs. Jeff Dew, Alan Hawkins, Jocelyn Wikle, and Chelom Leavitt for their guidance on this study.

1. For age at first marriage, I added a squared term to capture the possible curvilinear relationship between age of marriage and marital quality.