Motherhood doesn’t cost women as much with respect to future earnings as it used to, according to new research on the motherhood wage penalty from Wei-hsin Yu and Janet Chen-Lan Kuo. However, not all their new evidence will delight champions of equity: they also document growing class inequality as well as persistent gender differences when it comes to parenthood and wages.

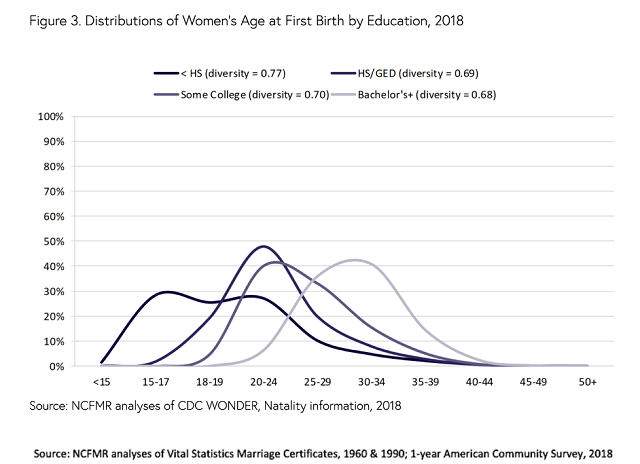

Let’s start with growing class inequality. On average, first births have been moving toward older ages fairly rapidly in recent decades. That was part of what motivated Yu and Kuo’s revisiting of the motherhood wage penalty, as they reasoned that motherhood might cost less at ages when work histories have already been established. However, there are important class differences in the timing of first childbirth.

Among those who have not completed high school, the most common age range for first births is 15-17. This not surprising because early first birth can interfere with continuing education. It is also a very small part of the overall story as most women in the United States do complete high school (those who do not are a small share of the population). What drives the class inequality story is that the modal age at first birth for those who have completed high school but do not have a four-year college degree is in the 20-24 range, whereas it is a full decade later for college graduates.

Where has the decline in the motherhood pay penalty occurred? Those who became mothers near or after age 30 no longer take a pay hit associated with motherhood. The wage penalty for women who had their first child before their late 20s has been fairly stable over time. That means that for American women without a college degree, motherhood costs every bit as much as it used to. The progress over time is only among relatively advantaged women.

Back in 2004, Sara McLanahan put forward a theory that family change is contributing to socioeconomic inequality that she called “Diverging Destinies.” McLanahan talked about how family change was contributing to better quality parenting and concentration of material resources among the already advantaged (children’s destinies were not just separated by their parent’s social class, but they were also diverging further because family change was not equal across social classes). But for McLanahan, maternal age was an indicator of parenting quality because of psychological maturity and greater likelihood of being in a stable union. In other words, it contributed to children’s nonmaterial resources, and she separately showed that material resources were diverging too, because the already advantaged had shown more growth in maternal employment.

Yu and Kuo’s new findings mean that maternal age is also an indicator of material resources: older moms do not incur the motherhood wage penalty that younger moms do. We already knew children’s destinies were diverging because more educated mothers were more likely to be employed. Now we know that because they are typically older, educated mothers have a greater wage advantage over their less educated counterparts than they used to.

A diminished motherhood wage penalty is an important step toward gender equity in wages. Previous work had shown that the motherhood wage penalty was highly resistant to social change. At last, it seems to have eroded. However, our delight about that progress must be tempered by the maldistribution of the gains at this point in time.

There was another piece of new evidence that Yu and Kuo introduced about inequality between men and women. Men experience a fatherhood premium—fathers have higher hourly wages than similarly qualified childless men. And women who become mothers at older ages now share this parenthood premium. This is finding is new: it is a reversal of the motherhood wage penalty rather than just an erasure of it.

But even older first-time mothers do not experience a real boost in income the way fathers do. How can this be? That’s because older mothers tend to reduce working hours, and they do not take a pay hit. They are paid the same for fewer hours, so the hourly parenthood premium leaves them at the same income level rather than a higher one. This points to a persistent gender difference when it comes to parenthood and wages: men’s parenthood premium increases income, and older mother’s parenthood premium increases the time they take away from work.

Laurie DeRose is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, and Director of Research for the World Family Map Project.